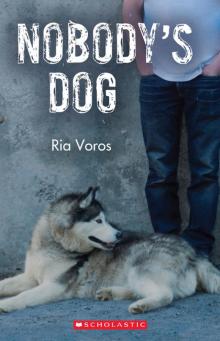

Nobody's Dog Read online

Page 3

She looks so sad for a moment I think I might have gotten through. But then her face crumples up in anger. “Don’t talk to me about problems, Jakob. My life’s been turned upside down too. I’m trying to do the best I can.”

I get up and put my plate in the sink.

“You’re my nephew. You mean the world to me. I understand —” She presses her fingers between her eyes. “I know we’re both still grieving.”

“Right. We’re grieving,” I say quietly. This is the point where we both look over the edge of the cliff, wondering if we should go into all the stuff we don’t talk about.

“Jakob, I’m sorry. I know it’s hard for you, but a dog isn’t going to happen right now. Can’t you see that?” And this is where she steps back, every time, so we don’t have to deal with the stuff for another day. It always makes me breathe easier, but a second later I just feel angry. Like something’s been grabbed out of my hands.

I head to my room, but she blocks my way. “I need to be alone now,” I say to her scrubs.

She puts her hands on my shoulders. “You’re a good kid. We’re both just trying to figure this thing out.”

“Whatever,” I say. “I don’t really care.”

* * *

Today’s Most Adoptable Dog:

* * *

Hello, I’m Buzz. I’m a Nova Scotia duck tolling retriever. I’m three years old and I love anything to do with water. If you want a best friend who can hike, swim and run with you for hours, come and take me home. I’m friendly and good with kids, and I’m well-trained. What’s not to like?

* * *

I can tell Aunt Laura feels guilty about our conversation because she rents us a DVD that night and we eat my favourite, take-out sushi, on the couch. It’s not a great movie, but she never gets ones I’d pick anyway.

The sushi’s not bad. She lets me eat all the dynamite rolls, which are my favourite. A battle breaks out in the movie between the hero and a hairy, pig-faced bad guy. We both groan at the bad special effects.

She sighs and mutes the TV. “I’ve got to pee. Can you handle the suspense until I get back?”

“Somehow I’ll manage.” I inhale another bite of sushi.

But when she sits down again, she doesn’t reach for the remote.

My jaw tenses up.

“I know this is hard, Jakob, but you really need to make some new friends this summer.”

I chew my sushi slowly so I don’t have to answer.

“Why don’t I sign you up for a camp — baseball or tennis?”

“Not sports.”

“Why not?”

“Not sports.”

“Okay, what about a drama club?”

I give her a look that says are-you-kidding-me?

“Well, what then? You have to get out of the house.”

“I don’t want to be in a camp. They’re for kids.”

“Seen yourself lately?” She gets up and fills her glass at the sink. “You can’t sit around here all summer.”

“I get out.”

“Yeah, but with other kids, I mean.”

There’s a knock at the back door. Soleil puts her face up to the window.

“We’re not done,” Aunt Laura says to me as she goes to let her in.

“Hey, upstairs neighbours.” Soleil rolls into the kitchen like she’s on wheels. She wears a short yellow dress that looks like it would come off if it was windy enough. It actually looks nice on her, though. Her hair’s all done and she’s wearing makeup. For a second I imagine what it would be like to go out with Soleil.

“Where’re you off to? A film premiere?” Aunt Laura’s all smiles.

“Better — a date! I haven’t had one in years.”

“I’ve forgotten what one’s like,” Aunt Laura says.

“Where’s Libby?” I find myself saying. I wanted to say it to break up the conversation, but it comes out sounding like I care.

“She’s downstairs watching an art documentary.”

I snort.

“Seriously,” Soleil says. “Spray paint art in a Brazilian ghetto.”

“Well, she can always join us up here,” Aunt Laura says. “Right, Jakob?”

“Uh, right,” I mutter.

Soleil smiles at me with shiny lips. “That’s really sweet. She’s hard to pry away from her obsession. I’ll let her know for next time. Feel free to pop down, Jakob, if you want.”

“Okay, thanks,” I say, thinking what I’ve just heard would be enough to keep anyone away.

“Hey, J-man, I wonder if you could do me a favour.” Soleil comes over and sits on the couch. She smells like peach perfume.

I don’t move over, even though her leg’s touching mine a little. “What?”

“Tomorrow morning we’re going out of town for a few days and I was hoping you could water our plants.” She eats a piece of pickled ginger off my plate. “I’ll pay you.”

I sit up. “Really? How much?”

“You don’t need to do that, Soleil,” Aunt Laura says. “He’ll do it any —”

“How much?” I ask again.

“Ten bucks.”

“Sure. You want me to do anything else?”

“Do you mop floors?” She laughs. “Don’t worry about it, J-man. The watering can will be on the counter.”

“That’s very nice of you, Soleil,” Aunt Laura says, and offers her a cup of tea.

“Thanks, but I have to get going,” Soleil says. “We’ll be back by the end of the week.”

She floats out and we’re left with the hero of the bad movie stuck flying across the TV screen.

“Well, that’ll give you one thing to do,” Aunt Laura says from the sink. The dishes clatter.

I stare at the TV for a few minutes, but it’s pathetic. The hero’s going to beat the bad guys and rescue the girl from the coffin she’s locked in. It’s always the same.

“You know, I heard there’s a mountain biking camp at the rec centre,” Aunt Laura calls over her shoulder.

I take that as my cue to exit. “I’m going to my room,” I say. “To read.”

“What about the movie?”

I let her figure that one out for herself.

Mom and I are making a cake for Dad — a surprise carrot coconut cake that he’ll flip over because it’s his favourite and we’ve been really good at pretending we’ve forgotten his birthday. Mom’s stirring in the flour and then the mustard — I know it’s a dream when I ask her about the mustard and she says it’s the secret ingredient. Let’s eat it for dinner, she says. You’re always asking for dessert first. Real Mom would never do that either — vegetables are really important to her. She asks me to get the milk, but when I open the fridge door there isn’t food on shelves, just a doorway onto a dark, empty street. I don’t want to, but I step through, and then I’m back in the same old dream: the heartbeat of the car echoes in my head as I start the search all over again. The streets are empty, silent and still, like a photograph I’m running through. The urge is so strong it chokes me, but I run faster — I have to find it.

I gasp for air and wake up on the floor in my room. The palms of my hands burn from the carpet.

I stand up slowly, try to focus on something other than my racing thoughts. The street lamp above Aunt Laura’s car lights the rain that falls on the street. I stare out for a long time, picture myself leaving the house, running out there, actually looking. What would I find? My eyelids get heavy and I shuffle back to bed. This time I only dream of blackness.

Chapter 3

* * *

hey dude — comix doesn’t have the issue of War Machines you asked about. hadn’t even heard of it. i found a bunch of old x-men issues, though. i could send you some. we’re going to france tomorrow to see my cousin. i hear french girls are pretty friendly if you know what i mean. you’ll get my report!

* * *

I water Soleil’s plants every day, Even though I know I’m not supposed to over-water them or they’ll die. I snoop around he

r apartment a little while I’m there. She and Libby are pretty messy. Laundry is piled on her bed and there are dusty books everywhere. Libby’s got games and an artist’s easel, but that’s about it. The suite only has one bedroom. There’s a single bed behind a curtain in a corner of the living room. At first I think Libby must sleep there, but then I realize Libby’s got the bedroom, right under Aunt Laura’s.

Soleil’s plants are really big and overgrown — one has legs made of baby plants that reach to the floor, even though it’s on a stool. I call it The Thing. In the kitchen there’s a jar of mini chocolate bars and I take a few. I think about watching TV down here, with the place to myself, but I can do that upstairs too — Aunt Laura’s at work. I find a stack of old sketchbooks beside Libby’s bed and look through them. It’s mostly birds and flowers and sometimes faces, but I have to admit, she’s not bad. I’m no artist, but Libby’s got some talent. I just wish she didn’t stalk me with it. I make sure the sketchbooks are back in the same order and in the same spot.

Each day seems to last twice as long as it should. On Wednesday I risk Aunt Laura’s wrath and rearrange the glow-in-the-dark stars on my ceiling into new constellations. I just make them up, trying to remember what my dad used to say about them, but they don’t stick well anymore and finally I have to toss them in the garbage. I try not to see my dad’s face in my mind as I do it. I wonder how long it will take for Aunt Laura to notice the peeled-off paint. I find two new adoptable dogs — Rusty and Ben — to add to my list. Aunt Laura tries to suggest more camps and clubs, but I just walk away and eventually she stops. I build a skate ramp and practise new tricks but almost break my nose. I take a photo of my bloody face and send it to Grant. He emails back a shot of himself on a beach in France. I watch Old Yeller but turn it off before they have to shoot the dog.

On Thursday I wander over to Mahon Park and check the notice board. The blue stickie is gone and there are no other jobs posted. Someone’s left a pair of sunglasses on the railing and I take them. On my way home I go into the corner store to buy a slushie. Grant and I used to get one for free because the people behind the counter never paid attention. I’d go up and pay for mine and Grant would sneak out with his under his shirt. Today I push my coins across the counter and watch the stocky, shaggy-haired guy drop them into the cash register. He looks like he’s in high school, probably working here for the summer. For a second I think of asking if I could get a job. How hard could it be to work at a corner store? I bet he gets free slushies.

“Uh, you okay?” The guy is staring at me.

“Yeah, fine,” I mumble.

“At least you’ve got a summer, man. I’m stuck in here all day.”

“Must suck,” I say. Do it, I think. Ask about a job.

Someone brushes by me, holding out a bag of bread. “Look, I bought this yesterday and it’s already mouldy.”

The guy gives me a look, then peers at the bread. “You-can-exchange-it-or-get-a-refund-with-a-receipt.”

I shuffle back into the hot sun.

On Friday Soleil and Libby come home and give me the ten dollars, plus a huge chocolate bar from wherever they went. I feel bad for eating the mini chocolate bars in their jar — all week I’ve been taking a few and it’s half empty now. Soleil doesn’t seem to have noticed. Aunt Laura pours her tea and they chat while I channel-surf through the usual crap.

“Jakob really enjoyed helping out with the plants,” Aunt Laura tells Soleil. “He was down there every day.”

“That’s so nice of you, J-man,” Soleil calls from the kitchen. “You can be my perpetual plant-waterer.”

“He needs to get into a club or something,” Aunt Laura tells her. “I tried to talk to him about the rec centre’s camps. I’m worried about him here the whole summer.”

“I can hear you,” I call back, and flick past some cooking show where they’re boiling lobsters. It gives me the creeps.

“It’s not a secret,” Aunt Laura says. “You’re moping around here —”

“I’m not moping.”

“You are. You’re sulking.”

Soleil makes a tsk sound. “Libby’d be happy to hang out you know, J-man. She’s home from art camp in the afternoons.”

Aunt Laura tries to sound encouraging. “That’s an idea. You guys could go to the pool or ride your bikes to the corner store.”

I stare at the weather guy explaining tomorrow’s highs. “No thanks. I’m fine.”

“Jakob, don’t be rude. Couldn’t you show Libby around? She’s still new here —”

“Oh my god,” I mutter. “Just leave me alone.” I throw the remote down and stomp to my room, slamming the door. At least that feels good.

It’s dark and cool in here because the curtains are drawn. Day number eight of the summer that lasted forever. I leave the light off and sit on my bed, wondering what I should do. Go on the internet? Read? Go to sleep? Dig a tunnel into the middle of the earth? Nothing sounds good.

Aunt Laura knocks on my door. “Jakob?”

“I’m sleeping.”

“We should talk about this,” she says.

Talk? You never want to talk.

I hear her sigh. “I have to cover a night shift for someone tonight. You’ll be okay?”

“Fine.”

Soon I hear the front door close and her car start up. I fumble around and find a flashlight in my bedside table and turn it on. The batteries are almost done. I watch the beam move over my closet, my computer screen, the closed door. I sit there until it fades out and dies.

We’re making a snowman, the three of us, and Dad’s found a top hat and fancy-looking cane for it. I have no idea where he got those but I don’t ask because I know I’m dreaming this. Around us, kids make snowmen with their parents — there must be dozens of families and dozens of snowmen in the park. Then I see it from above, as if I’m flying. Ours is the only one with a top hat. I’m looking for my parents among the families below when the snow starts to melt and everything goes brown, then black, and I hit the ground. Another strange, dark street and I’m wondering what just happened, but the need to search feels like it will burst out of my chest.

I wake up with the scratchy carpet on my cheek. My clock radio says 12:36. I pull open the curtains. It’s a full moon out there, lots of light to see by. There are shadows on the street from the cars and telephone poles. A full moon means you can see a lot better than other times of the month, but it also means weird things happen. Aunt Laura always says the worst injuries come into Emerg on a full moon. It’s like something happens to people’s brains — they act crazier than normal. And animals do too. The coyotes come out of Mahon Park and howl at the full moon.

Out on the street, something catches my eye. It’s a dog, a big grey and white one, trotting along the sidewalk. It stops to sniff a metal pole and then pees on it.

I open my window to see better and the frame creaks. The dog hears it, pricks his ears.

“Psst.” I stick my head out the window. “Over here.”

The dog turns and fixes his eyes on me. His tail wags a little. Just at the white tip. There’s no one else around, no owner that I can see.

Something inside me makes a decision. Actually, it’s someone: J, the guy who tried the highest rails on my skateboard and told Grant the dirtiest jokes. J says it’s time to go. I close my window and grab my hoodie from the closet. It’s not cold out, but I feel better having it. The hair on my neck stands up as I shuffle down the hall and take the quietest route through the kitchen to the back door. The floors are old and creaky and even though Aunt Laura’s not here, I don’t want Soleil or Libby to hear me. I grab my key from the bowl, close the door as slowly as I can and lock it behind me. The steps down from the deck are creaky too, so I take the first two and then jump past the rest, onto the crusty grass. There are no lights on in Soleil’s place.

My skin feels cool and prickly. It’s finally happening. No more running around while I’m asleep. I sneak around the side of the house and

open the gate. But what if the dog’s gone — or what if I imagined him? A memory flashes through my mind so fast I can’t catch it. It seems really familiar somehow, watching a dog out at night, but I can’t think why. Maybe it’ll come to me if I find him.

When I get to the pole I saw him pee on, he’s not far away, sniffing in our neighbour’s flowerbed. He looks like a wolf, but I’m sure he’s a husky. A girl in my grade seven class had one and it looked like this. Black and grey on top and white on the belly, with face markings like a wolf, and a grey tail with a white tip. His ears are black and they stick straight up, like fuzzy triangles. I want to feel how soft they are. Huskies sometimes come into the shelters, but lately they’ve been adopted really fast. I had one, Rex, on my list last month but he was gone in two days.

I stand there waiting, watching to see if he’ll run when he sees me, but he keeps sniffing, and his tail starts to wag like he’s found something good.

I walk closer. He scratches the dirt with his paw and pees on the spot. When he’s finished he looks really proud of himself and turns around to face me, like he knew I was there all along. We stare at each other.

“Hi,” I say.

He smells the air.

“Where are you going?” I ask. I look back at my house to make sure no lights are on. Everything is quiet, except for one or two cars passing on the main road a few streets over.

The dog turns and walks down the sidewalk, slowly, not like he’s running away, but like he’s going for a stroll. I follow. He stays in front of me, sniffing the grass and flowers, but I get the feeling he’s sensing me too. When he gets to the corner, he waits.

“Can I come?” I ask. It’s pretty stupid to ask a dog questions. “I’m J,” I say, because that’s who I’ll be tonight. I’m not Jakob Nobody or Jakob Nebedy. Not even J-man. I’m J, and tonight I’m going to do whatever I want.

The Opposite of Geek

The Opposite of Geek Nobody's Dog

Nobody's Dog